Across Africa Part 6: Down with Malaria

At first I dismissed the overnight headache as a bit of dehydration. It was gone the next day, but reappeared the following evening along with a fever. I’d been in Lusaka for several days by this point, enjoying a rest from the road and catching up with an ex-colleague I used to work with when living in Tanzania.

When the dizziness and vomiting started the next morning it was obvious something was wrong. After years of living and travelling in Africa (over 7 in total) I’d never had malaria, but the symptoms all suggested my time had come.

During my first visits to parts of Africa where malaria prevalence is high, I took prophylactics, (larium) but knew taking them in the long term wasn’t good for the body. And so the years I lived in Tanzania and travelled on the continent afterwards I just stayed mindful, covering up and using repellent when necessary, even thinking that perhaps I’d built up some natural immunity to the deadly disease, despite having never had it. How wrong.

I arrived in Lusaka with a rough plan to stay for about a week. It was almost one month later, fit and recovered from malaria (or at least I thought) when I rolled out.

The photos here cover my time in Lusaka, plus the following few days on the road afterwards. I didn’t get very far.

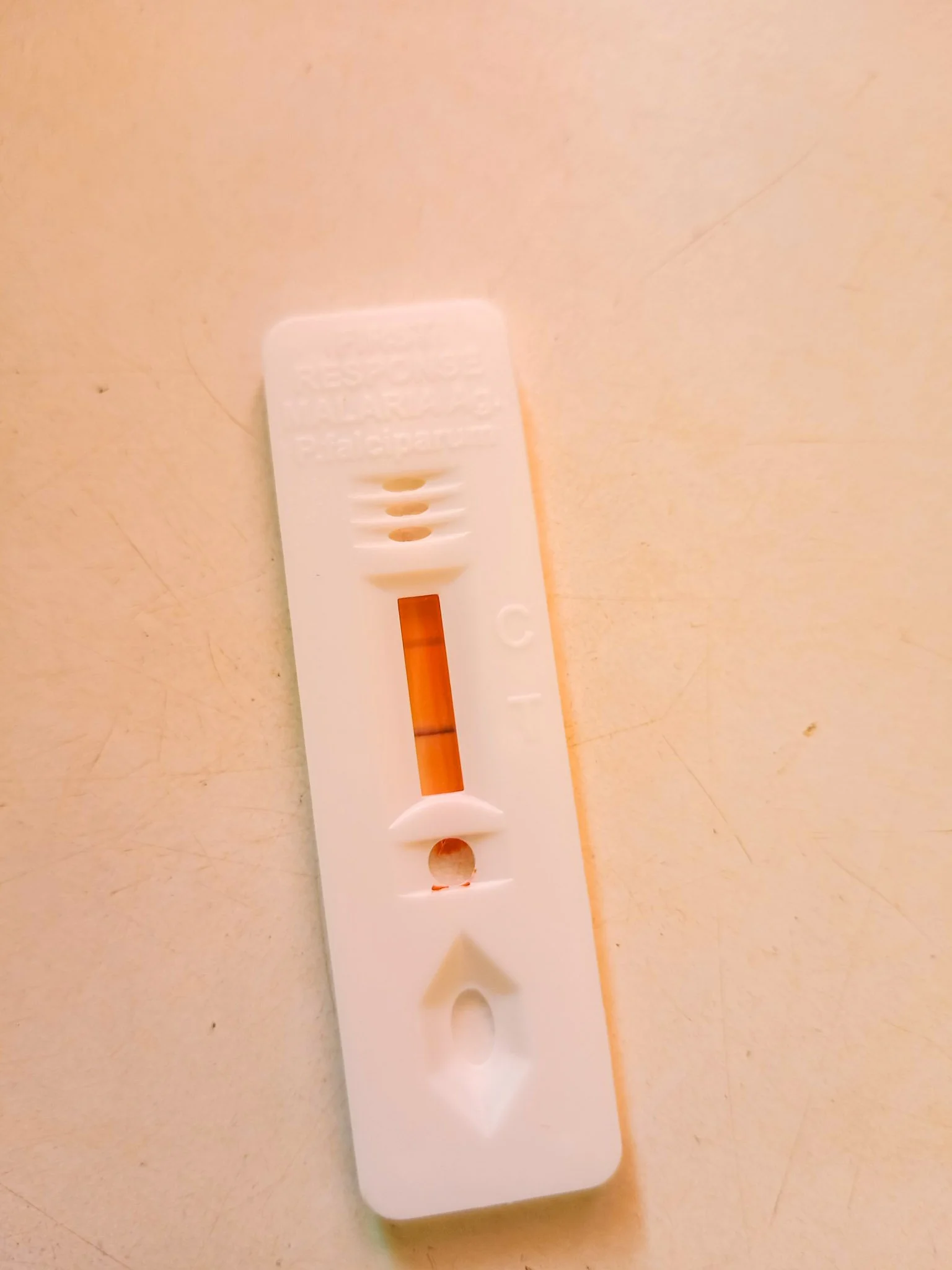

On the second morning after initial symptoms started I took a malaria test. A second red line on a rapid test kit means positive. As it was barely visible, and I wasn’t 100% sure I had malaria rather than something else, I decided to head to a hospital and confirm.

The report was conclusive, but by the time I’d received it I’d already argued with a member of staff who’d come to the hospital bed waving a card reader for payment in my face. Perhaps that’s how many private hospitals operate in Africa - pay first, treatment later. Nothing had been done at this point. I already had the medication to take should I contract malaria, so dismissed the hospital’s advice to keep me in overnight and put me on an IV drip. While I had medical insurance, I didn’t feel staying in the hospital was necessary, so discharged myself, a decision I regretted some weeks later.

There are a number of different strains of malaria and antimalarial medications. The most common strain throughout Africa, Plasmodium Falciparum, also happens to be the most serious and potentially fatal. I started this medication pictured the moment malaria was confirmed. The fever and headaches continued for the next 24-36 hours, but within a few days I was feeling fine again.

My host for the first week in Lusaka was a colleague from my years living in Tanzania. Now based at an international school in Lusaka, she invited me to speak to her daughter’s class about my journey.

Curious and energetic, like most 10 year olds.

I then shifted a few kilometres to stay with longer term residents of Lusaka, who knew someone I once hosted in Tanzania.

And found myself drinking a lot of this over the next few weeks.

New rubber. After 5000km or so of use, it was time to change the tyres. While one tyre still had plenty of tread and life on, the other was wearing thin, so it was easier to change both. Tyres like this are not available to buy in Zambia, so I arranged for them to be sent here.

I also arranged for a water filter to be sent to Lusaka. While not strictly essential (I’ve managed for years cycling in Africa without a filter), I knew that finding clean water on some of the tracks ahead of me in Zambia, and more specifically Angola, might be difficult. As the filter is so lightweight, I decided it was worth carrying.

I also managed to get a new sleeping mattress sent, so no more waking up in the middle of the night with a semi-deflated mat.

As a lot of the ground in Africa is thorny and/or rocky to camp on, I decided to find something to provide an extra layer of protection between the tent and groundsheet to safeguard future punctures of the air mattress. It just so happens that a sunscreen protector for a car windscreen, cheap and lightweight, is the perfect solution.

And would fit conveniently underneath my tent.

I also picked up a better mini-tripod. The one I started the trip with broke, and the little silver one was really too small and weak to support my mirrorless camera.

I really only use a tripod these days for night-sky photography, so having a much larger tripod (as I used to carry) didn’t seem necessary.

Leaving Lusaka. A longer stay than planned, but surrounded by good company and an opportunity to rest and relax with kind hosts, I was in no rush to get back on the bike. It was several weeks since I’d recovered from malaria. I had a mild headache on this morning of departure, but attributed that to alcohol the night before.

But that first day of riding out of Lusaka didn’t feel right. The headache continued, so I stopped in a village clinic and asked if I could have a malaria test. As malaria is commonplace throughout Zambia, medical clinics are used to dealing with patients requiring malaria tests and medication.

The result came back negative, with the nurse and clinician thinking the headache was more likely a case of dehydration. I spent a few hours resting on a bed in the clinic taking oral rehydration salts. This cleared the headache, so I felt comfortable to continue riding.

And then the clinic decided to give me more oral rehydration salts and condoms for the journey. I’m not sure why they decided I should carry extra condoms with me, but I left a donation and got back on the road.

The rainy season, which was coming to an end when I arrived in Lusaka, was now over, meaning the months ahead should make camping easier.

Morning after the first camp out of Lusaka. I didn’t sleep well and the headache was still there. I wasn’t 100% sure that the negative malaria test the day before was accurate, so decided to ride to the next clinic and test again.

The 40km ride to get there was a real effort. Aside from the headache, I had almost no energy. This clinic was bigger than the one I was in the previous day, but like most rural clinics in Zambia, facilities were basic. In recent months, many health care facilities in Zambia, and other African countries, have had to deal with one of their main donors (USAID) pulling funding out of Africa.

It was actually a relief to find out I had malaria again, rather than something else. As it was only several weeks since the initial infection, it’s quite likely I never fully cleared the malaria out of my system to start with. And so my decision to discharge myself from the hospital in Lusaka is one I regretted.

I had no energy to move so the clinician showed me to a room where I could rest while taking a course of anti-malarials. I explained to the clinician that this malaria was most likely the same infection, so he administered a stronger medication. While it was effective in bringing down the fever over the next 24 hours, I later realised that the dosage given to me was only that for a child.

This is the medication I should have taken in the hospital in Lusaka, but 60mg, which is given to me as single dose, and then repeated 12 and 24 hours later, is the dosage for a child weighing around 25-30kg. As my weight is somewhere between 75-80kg, I needed to be taking a dosage of 180mg each time, which the village clinic does not have.

Despite being under-dosed, I felt strong enough 2 days later to ride again, so left the clinic and thanked them with another donation (they weren’t going to charge me). I was only 100km from Lusaka, and briefly considered returning, but there was a district town and hospital 50km away, which I knew I could ride to in a day, so that made that my plan, hoping they would have better medical supplies.

At the district hospital I tested again for malaria. I was still positive, despite having no symptoms, but these tests still show a positive result weeks after the initial infection.

I was able to find the correct dosage of the medication I needed, then asked the district hospital to administer it 180mg at a time over 3 doses (0, 12 and 24 hours)

With the correct dosage, I was more confident this stronger medication would eradicate the malaria from my body. Despite having no symptoms, I decided to stay in the district town of Mumbwa another week before riding again.

Here I go again. Medication finished and feeling fine. I decided I would ride on and continue with the journey, stopping at the next major hospital to check if there were any malaria parasites still lingering my bloodstream.

If you enjoyed this post, and any other, please help support the website and ongoing content creation. It’s a great motivation to continue sharing my two-wheeled travels. Thanks