Across Africa Part 8: Where the road ends. Into Eastern Angola

Once upon a time, Angola was a difficult country to visit. Civil war started the moment the country gained independence from Portugal in 1975, and continued for 27 years. During that time, over half a million people died, and more than 10 million landmines were laid.

In more recent post-war years, travelling to Angola required a visa in advance, which is not uncommon in parts of west and central Africa, but often costly and difficult to obtain. In comparison, most countries in east and southern Africa provide visas on arrival for many nationalities.

As a means to boost tourism, in late 2023 Angola relaxed its entry requirements, allowing many nationalities to enter the country freely for up to 30 days. For longer stays, an E-tourist visa can be applied for online, allowing that 30-day stay to be extended for a further 60 days, at minimal cost. I wasn’t anticipating staying 90 days, but knew that 30 days wouldn’t be sufficient to cover what I estimated to be around 2000-2500 km of cycling.

While I have visited a number of countries in east and southern Africa more than once, it would be my first visit to Angola.

Aside from a few articles describing how oil money had made its capital one of the most expensive cities on the planet, the rest of the country—where I would spend most of my time—was a blank slate.

Fortunately, I had some support. In the weeks and months before arriving, I’d been in touch with an Angolan working on a major conservation project in Africa. His knowledge, local connections, and generosity were of great help once I arrived in the country. More on that in the posts to come.

As usual the photos here appear in chronological order, and cover the first 600-700km of cycling through eastern Angola.

Africa’s 7th largest country has a population of 38 million. Like most African countries, it is experiencing rapid population growth, having doubled in population in the last 20 years!

My route through Angola was no more direct than it had been through Zambia. Almost all the roads/tracks in the east of the country were unpaved. In total, I cycled just over 2700 km during 2 months in the country.

The border and customs post at Karipande, where I entered Angola, was about as simple and remote as international border crossings go. No power and no mobile network. Few questions were asked as I received a 30-day Visa on arrival stamp in my passport, with the customs official having a quick check of my bags before I was given the green light to continue.

The road into Angola was nothing more than a sandy track. 2.8” wide tyres were at their most effective during these first few days in Angola. It took most of the remainder of the day to cover the 50 km to the first settlement marked on my map, with the sandy track cutting through miombo forest close to the banks of the Zambezi River.

Baby cobra on the banks of the Zambezi River. I was looking for a place to camp beside the river, but realised the holes in the sand I kept seeing were most likely those created by snakes.

Sunset over the Zambezi. Africa’s fourth largest river begins its journey in Zambia, but then flows southwards through eastern Angola for around 280km, before re-entering Zambia.

The snake holes in the sandy banks of the river persuaded me to set up camp a little further away from the water on my first night in the country.

Detour time. While I could have crossed the Zambezi here and headed west, concern about how sandy the road might have been for the coming days put me on a 400 km or so detour, meaning I would ride north towards the border with the DRC, before turning west.

Boys and their toys. It became apparent on my second day in Angola just how neglected this part of the country is. There are no schools in such remote rural areas.

Other than a few motorbikes, I saw just one 4-wheeled vehicle during the first two days in the country. I had carried food to last a few days until I reached the first town.

Water was not so much an issue to find as I crossed a number of small rivers to fill up from.

The absence of schools was very noticeable. During the years of civil war many people fled the countryside and moved to large cities where security was greater. This was the first school building I saw, although the school didn’t seem to be functioning.

In the absence of schools it means the majority of children who grow up in rural locations like this receive no formal education at all.

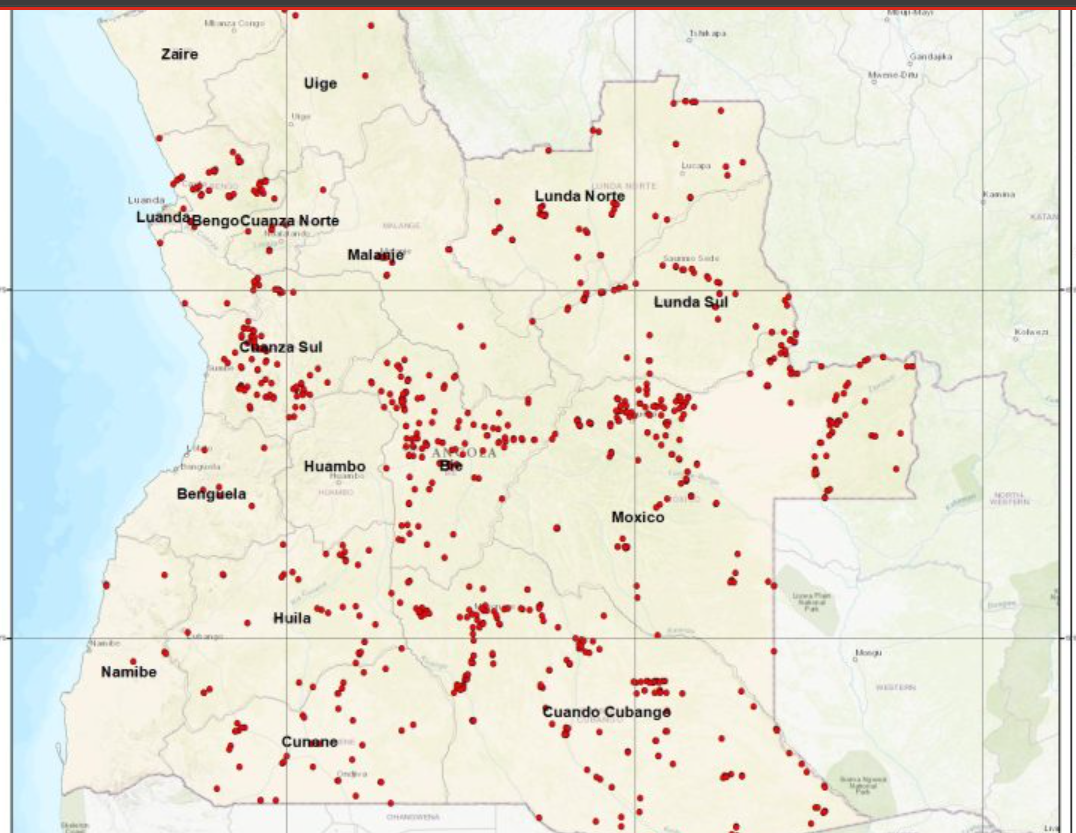

The high elephant grass on my second camp in the country kept me hidden from the road here. Before arriving in Angola I was well aware that parts of the country still had areas of land that hadn’t been cleared from landmines.

Fortunately most areas that have remaining mines are either so densely vegetated I would never be able to access them, else they are marked with red and white sticks in the ground to show it is an area containing mines.

On the third day the sandy track had become more pronounced as I approached the town of Cazombo. It was now May, and the rainy season had fortunately finished.

The small town of Cazombo had no accommodation, so I decided to ride to the Catholic Mission nearby and ask if I could pitch my tent. After a short time I met one of the sisters who spoke English. A simple room was made up for me and they invited me to eat with them.

Shopping in Cazombo. If you travel in west or central Africa the sight of these red tins is a familiar one.

Morocco is the world’s leading exporter of tinned sardines, which can be found throughout west and central Africa, (not east and southern Africa curiously) almost always in these flat-packed red-coloured tins, costing around $1 a tin. Easy to pack and nutritious, I would usually be carrying at least a few of these in my panniers.

Crossing the Zambezi at Cazombo.

Old bridge and new. Most bridges over major rivers in Angola were blown up during the civil war, so those that exist date from the last few decades, often with the previous one alongside.

Water fill up. There was an absence of bore-holes in eastern Angola, so I filled up water either from streams or wells in villages like this, either filtering it to drink or showering/cooking with it.

And any stop in a rural village in Angola would draw a crowd of mostly young faces.

While the rains had finished, it was evident from some of the tracks that there have been heavy rainfall in the weeks and months previously.

A bombproof set up. Such tracks quickly make a mess of a bike, but without a chain or cassette to worry about, no amount of mud really makes a difference on a bike with a pinion gearbox and carbon belt.

Much of eastern Angola is sparsely populated and covered in woodland. Wild camping was not particularly difficult, but I was always mindful of straying too far from worn tracks.

There is little in the way of shops and local markets in eastern Angola. Moxico province is one of the poorest and most sparsely populated in Angola, so options for food outside of towns is limited.

Doxycycline. I started taking this antimalarial antibiotic following my second bout of malaria in Zambia, but noticed my skin becoming burnt in the weeks that followed. Doxycycline is known to increase the skin’s sensitivity to the sun, and despite using SPF 30 cream, I found parts of my body were burning (toes, neck, ears, lips, legs) to the extent that I decided to stop taking the antibiotic after the first few weeks in Angola.

Camped in high grass a short distance from the border with DRC. In the rainy season much of this land would be impossible to camp on.

Following faint tracks. I had already made a massive detour, so when the opportunity to take a short cut along a disused track presented itself, I decided to take it. Tracks which are no longer used can quickly be reclaimed by the bush, but this 50km stretch through high grass was still rideable for two-wheeled vehicles.

Meeting the railway. Angola’s railway network was destroyed during the civil war, but its principal line, the Benguela Railway, was reconstructed by the Chinese and is now in operation. The railway connects the DRC with the Angolan port of Lobito.

The small station of Mucussueje is close to the border with the DRC. My plan for the following several hundred kilometres was to follow it west.

Jimmy the Zambian shopkeeper. Finding anyone who speaks English is rare in much of rural Angola, where Portuguese, or more likely native languages, are more common. So it was a welcome surprise to find this shopkeeper and his brother, who were Zambian, working in a small store beside the railway line.

Following the railway. While my map depicted a road a short distance away from the railway, I realised there was no actual road when a motorbike sped by right next to the railway itself. So I wheeled by bike a few hundred metres over to the single gauge.

And then followed an almost exact straight line on this single track for the next 200 km.

The Benguela Railway at this point runs alongside the Cameia National Park, a huge expanse of grassland that forms part of the Zambezi river basin. Despite there being masses of open space and almost no-one living here, finding somewhere to camp proved challenging.

For much of the year this grassland is flooded, with the waters providing a source of fish for local communities living in makeshift shelters alongside the railway.

Bicycles are rare in Angola. Many of those in use are more likely to be loaded with cargo and pushed rather than ridden. This bicycle was loaded with well over 100kg of goods.

Police presence. As foreign travellers remain rare in Angola, especially in rural areas, anyone who travels here independently will attract the attention of police, who I quickly realised were merely concerned and acting for my safety. I was never asked for money, which is a notable difference from travelling in a number of other African countries, particularly those in west and central Africa.

Check-in. My Angolan contact had given me the address of a hotel I could stay at in Luena, the provincial capital of Moxico. After 10 days or so in the country, camping except on 1 night, I was looking forward to a few days rest. Most modern buildings like this in Angola have almost certainly been built by the Chinese in the last few decades, although I saw very few Chinese during my entire time in the country.

Large, clean and quiet, although somewhat soul-less. I was happy to have a place to rest while I planned my route ahead through the country.

And happy to find somewhere selling cooked food, which I hadn’t found in the countryside. Chicken, rice, beans and spinach here for about £3.50.

Good food and good value. It was about 1200 kwanza to the £1. I went back to this restaurant several times in Luena.

Relics of the past. The colonial infrastructure, when Angola was still under Portuguese control, remains in places. Sadly I saw little modern investment in revitalising or renovating what is old, preferring to knock down or just build new. Many buildings, like this former cinema, remain derelict.

Peace memorial. It was in the city of Luena where the 2002 peace agreement to end the country’s civil war, was signed.

Newly built and predominantly empty (I went several times), it was a welcome surprise to find a large supermarket on the outskirts of Luena. I realised that in order for produce to get here there must have been a paved road out of the city. That would have been the easy route out, but my journey through Angola still had plenty of dirt-track adventures to come….

Enjoyed this post? You can support my travels and ongoing content creation by clicking on the link below — every little bit helps keep the adventures coming!