Northern Uganda: Mwanza-Muscat Part 5

Not many people visit northern Uganda. This is understandable. For a number of years most areas were considered off-limits as a rebel group known as the Lord's Resistance Army terrorised villages and communities, effectively dividing the country in two.

The LRA and their infamous leader Joseph Kony no longer operate from Uganda, but places ravaged by years of destruction, child abduction and neglect don't recover all that quickly, and memories for people don't fade.

I had this in mind as I moved north from Arua. The road was actually only a few years old - a smooth ribbon of tarmac cutting a wide swath through a peaceful countryside of conical straw-hut villages.

The larger settlements, still villages, but usually labelled trading centres in Africa, consisted of more concrete buildings. Most of these were covered in bright paint advertising the companies who had obviously paid for this lurid spectacle. Soap powder, mobile phone, solar panel and of course paint companies dominated. The scenes on the roadside could have been from a number of African countries.

There would typically be a small shop of some description, a wooden bench or two outside and perhaps a tree providing shade nearby. Within that shade sitting on those benches would be anything from two to a dozen plus boys or men. A few motorbike taxis might also be parked alongside. The people were always male of course. Just sitting, passing the time. Sometimes there would be a game of cards taking place. Other times it just appeared like people were waiting for something to happen or someone to arrive. At least that is how I interpreted it. I imagined there must be hundreds of thousands of people in the countryside, maybe millions, doing precisely nothing for most of the day. Too hot perhaps, although the women were working.

None of it surprised me. I've seen it everywhere in rural Africa. I would wave, attempt a greeting and pedal on in the heat, wondering what discussion would follow in my wake.

The languages in fact changed too often for me to keep track of. In an area where Uganda, DRC and South Sudan - countries with years of instability and the subsequent movement of people, come together quite closely, I suspected there must be a complete mix of ethnicities. At least where English didn't work so well Kiswahili sometimes helped.

The children mostly seemed to entertain themselves with what nature provided them with. Had the water been clearer and cleaner I might have joined an excitable bunch as they hurled themselves off a bridge near some rice fields one afternoon.

One of the most noticeable man-made features in many of these settlements were the churches. Uganda is predominantly Christian and there were no shortage of large missions on the roadside. Each one seemed to be demarcated on google maps. Little else was.

The landscape remained green, but the sun became hotter as I left the tarmac and descended back towards the banks of the River Nile on a dusty track.

I was hoping the heat would actually dry out my GPS. It had stopped working in Murchinson Falls National Park following the mother of all rainstorms. I'd left it on the bike under blue skies for a few hours when I'd taken a trip up the river. The following morning when I packed-up to leave it went into a beeping frenzy and then switched itself off.

For the next few days I observed the screen fogging-up as I had it charged into the e-werk electrical converter that is connected to my dynamo hub. Power was obviously going into the device as the battery was charging, but none of the buttons were responding.

In the town of Koboko a guy working in a phone-repair shop opened it up with a tiny screwdriver. No sign of moisture so I followed the advice from others on the Internet which was to leave it in a bag of rice for several days. A 1 kg bag of local rice was duly purchased and I crossed my fingers that this would do the trick. To date there remains no sign of life.

Fortunately my smartphone can easily log the rides using the GPS function and be charged from the dynamo hub.

The Nile ferry crossing at Laropi departed 30 minutes before schedule. This rarely happens in Africa (it's also a free service which is even rarer), but no-one seemed the least bothered because sitting in the heat beside a collection of wooden shacks serving tea and snacks provided little joy.

I slept in simple lodgings most nights (£2-£5) and washed my shirt and shorts from dust and salt stains while I showered with cold water. It often seemed somewhat pointless as it would only take a few large vehicles to pass me the following day on the road to return my body and clothes to the state they were in before. Still, wearing something cleanish in the morning is a better start to the day than putting on dirt-encrusted clothes. When camping there is of course little choice unless one is fortunate to be next to a source of water.

I thought I heard a gun fired at my back one day on the road into Gulu. Within seconds the rear tyre had gone flat. I pushed the bike off the road and inspected it. A huge hole appeared in the middle of what are often dubbed indestructible tyres by touring cyclists. How had this happened?

For a number of weeks a split in the wall of the same tyre had occasionally pinched the inner tube and caused several punctures. Earlier on the same day the tyre blew-out I'd patched up a large tear in the tube and continued riding. Under what was obviously tremendous pressure I later cycled over a splint of metal, which not only caused the tube to pop again, but pop with so much force that it blew this hole through the tyre profile.

Fortunately I was carrying a spare, although hadn't expected to need this for some time, if at all on this tour.

North from Gulu I imagined a narrow bush track would lead towards Kitgum and the border with South Sudan. Several years ago that might have been the case. Now the track has been widened and graded. I suspect in the next few years another smooth black ribbon.

This track widening continued north of Kitgum - a new highway of sorts connecting Uganda with South Sudan, although for the moment there is practically no traffic other than work vehicles.

I had no idea what the Ugandan border post with South Sudan was called or whether it even existed.

I pulled over alongside a huddle of women beside a collection of grass huts. At first it looked like they were filling 20 Litre jerry-cans with water. But the jerry-cans were partly inflated and there was a sweet smell of alcohol in the air.

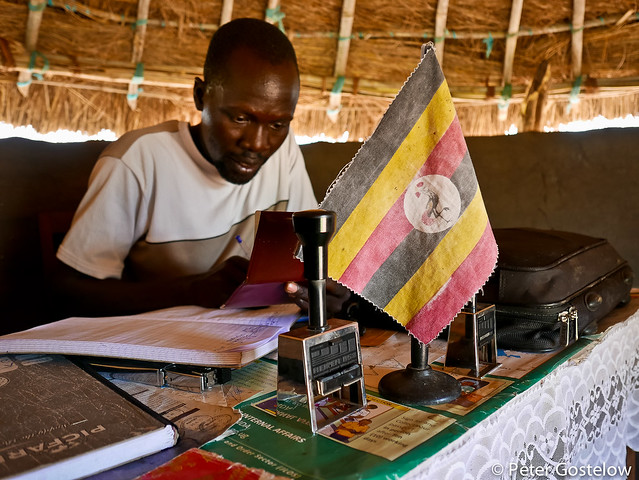

'That's gu', said the immigration official as I sat in the cool shade of another conical hut a short distance away some minutes later. 'It's a mixture of maize and sugar. Very strong. They will walk over there'. He pointed to a line of green mountains in South Sudan. It looked so far away.

'So you're a missionary'? asked the official as he continued to write down my passport details in a notebook.

'Do a lot of missionaries come through this way?' I replied, before explaining he could write 'teacher' instead.

'They used to'. Just a few Ugandans come through here now.

'So where is the South Sudanese border post?', I asked another official as I stepped back out into the glaring sun.

'It's 22km away', he said pointing down the road on which these women were now walking. I said my goodbyes and hoped the entry into South Sudan would be equally as smooth.

The route for this section of the journey, up to Kitgum, can be viewed here